Finding a Place To Belong: On Being Pākehā

- lauraalpe

- Nov 14, 2022

- 14 min read

Updated: Oct 15, 2025

As a Pākehā, I've spend my whole life in pursuit of belonging.

I’ve always struggled to fit in. Always felt different to those around me. Be it in Māori circles or Pākehā ones, or when I’ve lived overseas.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve loved learning other languages and immersing myself in other cultures.

This was always a great motivator for my travels and I still do get a buzz from being in cultures drastically different to my own. But the older I get, and the more self-aware I become, now I see that what’s really been behind this fascination with other cultures has been my unmet need to belong, and perhaps more importantly, to really know myself.

I’ve been meditating on this a lot lately, particularly during my recent experiences of receiving criticism on social media for my use of te reo Māori in my business name and activities. I’ve chosen not to take the flak personally, but to take it on as constructive feedback that can help me to deepen my own cultural expression of who I am. More on this later.

I want to explore a few significant memories, particularly as they relate to my interaction with te ao Māori, as they may bring some clarity around my own identity as Pākehā, and perhaps be of relevance to other Pākehā/tauiwi as they navigate their own identity in relation to Māori.

1986: One of my earliest memories was of attending my great-grandad George Laurenson’s funeral. George was highly respected in Māoridom and the Kīngitanga in particular due to his work as a Methodist minister to Māori communities, and the Māori queen Te Atairangikaahu and her entourage paid their respects during his poroporoaki.

I was 4 years old, so the memories are a bit vague. But I do remember the significant Māori presence and the beautiful himene, which made a lasting impression on me. My grandma (George’s daughter) passed down a lot of stories about growing up in and out of te ao Māori, and I know we shared a great reverence for the culture.

Our first home was in Glen Eden (West Auckland), which in the 1980’s was a cultural melting pot of Dalmations, Māori, Pacific Islanders and Pākehā. Our school, Prospect Primary, was a multi-ethnic, low decile school that reflected its working class community.

I remember learning waiata and making kōwhaiwhai art. Doing kapahaka and Pasifika dance in the school hall. Attending school fundraisers led by the school’s Pasifika community and marveling at how much money these humble, generous families would stick onto the oiled dancers.

I remember a distinct feeling of being at ease in that community.

In fact, when we moved house to Lynfield and started attending a higher decile school up the road, I experienced what felt like a reverse culture shock. White, rich girls bullied me for being the new kid (and a geek), and I longed to return to the comfort of our humble school and friendly neighbourhood.

1993: Form 1 at Blockhouse Bay Intermediate School. There was a guy called Manu (not his real name) in my class who used to pick on me. He used to call me shorty, shrimp, Pākehā (back when we thought it was a swear word), nerd, geek, and many more words that I’ve since forgotten.

Anyway, I don’t remember much about Manu, other than his shoes that could talk.

He had beat-up nomads. You know, the ones with the gummy, rubbery soles, and the thick leather with really visible, inside-out seams. Kinda like Charlie Brown shoes. Which I remember being cool in the 80’s. But this was the 90’s, so he must have inherited them from his tuakana or something. Come to think of it, his uniform was kinda shabby too. And he didn’t have lunch that often. I think he asked me for my kai a few times.

I didn’t understand at the time why he was picking on me. All I knew was that it didn’t feel good.

But now that I reflect on the situation, could it have had something to do with my aryan blonde hair, fair white skin, and blue eyes, all symbols of my white privilege? Or was it the fact that the school system was designed by and for people like me, not people like him, and it had me win every time? Or was it natural jealousy for my daily lunches, new school uniform, stationary, and new shoes? Or all of the above?

1995: Third form at Lynfield College, and not only had my school changed, but my church changed, as my minister dad’s job changed. And in the life of an angsty, insecure teenager, this was a social catastrophe.

We moved from a really white, middle of the road Anglican church in Blockhouse Bay, to a bi-cultural Māori/Pākehā Apostolic church in Kelston. Time for another culture shock. I remember our welcome resembled a pōwhiri, and we did a kind of whakaeke (procession) into the hall.

There were hīmene Māori that I’d never heard before, with electric guitars and a drum set pumping out funky rhythms. There were some native Māori speakers there too, which I didn’t appreciate the awesomeness of at the time. Everyone seemed to be related, and whānau were multi-generations and really big. Every time a baby was christened our congregation tripled in size.

And I do remember the kai. Definitely bigger than the biscuits and tea at the old church. I must admit, boil ups and doughboys were all new to me, and I didn’t appreciate it then as much as I do now.

The greatest thing about being 13 was that these culture shocks were short lived, and soon enough, life in our new bicultural/multicultural church became normal.

I made a new friend at church called Vanessa (not her real name) and we were both 13. Vanessa and I seemed to live on opposite sides of the train tracks. I was a girly-swot, busy studying and learning musical instruments, whereas Vanessa was busy preparing to have her first child.

When Vanessa’s parents found out about her being hapū, they were not impressed. But soon enough love won out, and that baby was raised in a multi-generational home with so much aroha.

As different as our cultures, upbringing and life situations were, we connected. I’m grateful for our friendship that opened my eyes to a whole other reality, which showed me the beauty of tikanga Māori and whānau support. Vanessa and her whānau are still in my life today.

These experiences were really formative as I navigated the world as an insecure, anxious teenager, unsure of my place and desperately trying to belong. And they impressed upon me the values of loyalty, acceptance, and aroha - unconditional love, that this little West Auckland corner of te ao Māori seemed to embody.

1998: 6th form at Lynfield College. There was a prefab that was used as a Marae where Māori students hung out and used the kitchen. I only went there once, for international culture day when my Japanese Club made sushi as a fundraiser.

Yes, I was in the Japanese Club. Anyway, the point is, te reo Māori was not on my radar at all, but Japanese most definitely was.

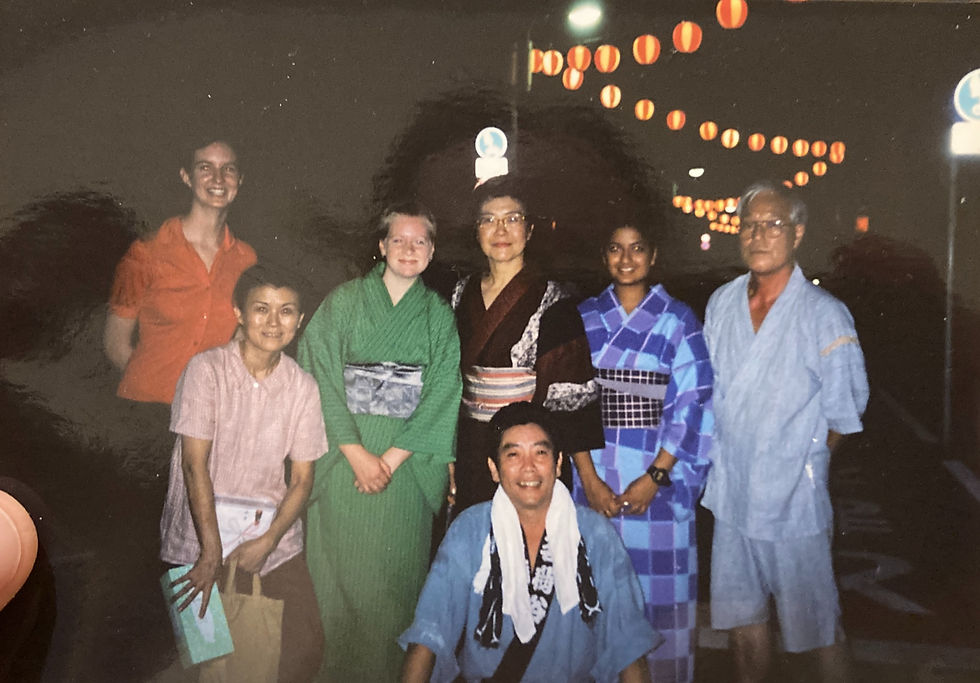

In fact, our class went to Tokyo that year, and my school helped me to get a scholarship to live in Japan the year after 7th form. If I’d been obsessed with Japan until then, living there for 9 months put an end to that, as I realized just how different our cultures really were, and how I wasn’t ready to live there long-term.

I can pretty much skip past the next 8 years, except to say that a big theme here was a desire to escape Aotearoa New Zealand due to an incredible feeling of claustrophobia.

It’s safe to say that I felt no pride in being a ‘New Zealander’. I thought ‘New Zealand’ was boring. Each summer I went on road trips where I’d keep running into the ocean, and I felt like I was sitting on the smallest island in the world. Where nothing happened. And life was boring.

There were adventures to be had overseas, I just knew it. Life would be interesting overseas. I would be interesting overseas.

You know what happened overseas? I missed home.

And I didn’t know what about home I actually missed, cause when I left home, I couldn’t think of a single thing to keep me here. I’d essentially moved from one British colony to another British colony. Same, same, right?

But when I was living smack bang in the middle of Canada in what some say is the indigenous capital, Winnipeg, brushing up against so much indigeneity got me wondering about tangata whenua back home.

In fact, when Canadians asked if I could say something or sing something in Māori, I was always ashamed at my lack of knowledge, so I made a vow to learn te reo Māori when I got back.

The year was 2008. Facebook was just for college students. Flip phones were the norm. Instagram was just a twinkle in someone's eye.

Te reo Māori courses were not as plentiful or as popular as they are now. But despite that, I was incredibly lucky to get a seat on Te Pōkaitahi o Te Ataarangi ki te Tonga o Tāmaki Makaurau, in Ōtāhuhu, a one year full-immersion course where English - te reo Pākehā was pretty much banned, with the catch phrase: “Kaua e kōrero Pākehā.”

I’ve spoken a little about my reo journey in another post and so I won’t go into too much detail, but I will share a couple of significant events as they relate to my pursuit of belonging.

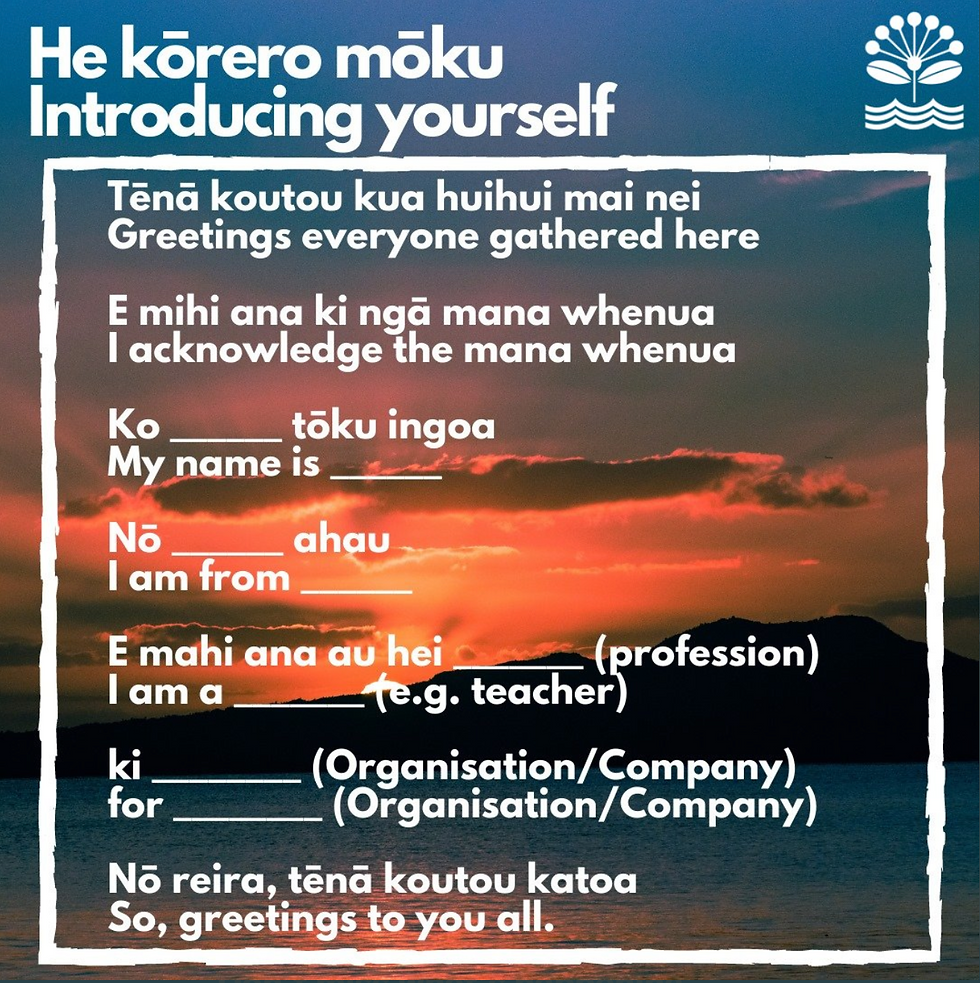

In the second week of school we all had to learn our pepeha. Sounds straightforward right? Memorise a few lines and get up and say it.

In actuality, learning your pepeha is anything but straightforward, for Māori, Pākehā and tauiwi alike. Whose pepeha do you use? What order should you say things in? What if you haven’t been to that marae yet?

And for Pākehā, it gets even more complicated.

What presented as a simple task actually felt like an existential crisis.

Where on earth is my maunga -ancestral mountain? Should I use one from Ireland, England or Aotearoa? Am I even allowed to use one from here if I’m not tangata whenua?

The only things I knew with certainty were my iwi: Ko Ngāti Pākehā tōku iwi, and my waka: Ko Dauntless tōku waka, and everything else was a confusing, guilt-ridden mess.

I remember crying my heart out in the bathroom to my Māori classmates (awkward), cause I had no idea how to actually relate authentically to this intrinsically Māori worldview.

I cringe hard now thinking of how bloody privileged I was to even be there, and how me crying on their shoulders was another act of taking up space. Yes they were so, so generous with me.

Being the only Pākehā in class for 2 years (and then 3 more in my Māori teaching degree), I did what anyone else might would have done in my place. I used the same template my Māori mates used, and inserted local West Auckland maunga, moana and awa.

It felt clunky and not quite right, but my kaiako didn’t really have the time to guide me in this, given that the course was really for Māori to reclaim their reo and tikanga, and I was the white anomaly.

2010: In the second year of my Ataarangi course my kaiako encouraged me to go back further and explore my ancestral connections in the UK. So I wrote to my nanna’s second cousin in Northern Ireland asking about significant mountains and waterways, and she wrote back saying that these landmarks weren’t of much importance to our people over there. Back to the drawing board.

So not having much more of a clue, I pushed on, and wrote pepehā using the mountains of Mourne and Strangford Loch, both places I’d never actually seen. Once again I felt like a phony. Neither my pepeha with Aotearoa landmarks nor my Northern Irish one felt authentic.

2015: It wasn’t till I started teaching in the Māori unit: Ngā Uri o Ngā Iwi at Westmere School that I had some cultural guidance from my team leader Jane Cooper, fellow Pākehā with decades of involvement in te ao Māori. She was quite adamant that Pākehā shouldn’t use pepeha as we have no whakapapa to these ancestral landmarks.

I struggled with this at first, as I so clearly wanted to find a way to relate to Māori. But over time I came to adopt her view, and I have come to accept that Māori and Tauiwi pepeha will and should always be different, to reflect our different relationships to the land on which we stand, one as tangata whenua, the other as manuhiri - a guest.

2016: I fell in love with a local Māori boy, and within a short time I had moved onto his pā - village in the heart of the city (Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland). I felt a sense of relief to not have to rely on my own fragile pepeha to culturally locate me. Now I could relate through my tāne’s whakapapa, especially as I was teaching all his nieces and nephews at the local kura.

I finally felt the dots connect. It all made sense. I finally belonged. Or did I?

2018: As part of my recovery from burnout, I traveled to the UK to visit my sis and explore my own whakapapa there. I’ve written about this trip in another post, but what really impressed upon me was how even in the Shetland Islands where I felt the strongest sense of spiritual and ancestral connection, I still did not feel like I belonged. Yes, I visited my ancestors' graves and our old stone ruin of a homestead, but I could not call this place home in a present day sense, only an ancestral one.

As far as pepeha research, it was pretty disappointing too. I couldn’t find a maunga of any decent height, and the closest thing I found to an actual landmark was the bay where my ancestors used to hunt whales named Whalwick (which was pretty cool).

And I especially did not feel any sense of belonging in Northern Ireland where I experienced an intense Pākehā dissociation, given how my Protestant Scottish ancestors displaced Catholic Irish some 400 years ago in the organised Ulster plantation. I simply felt ashamed and wanted to leave asap.

In fact, rather than belonging, what lingered was a deep understanding and compassion for why my ancestors left their homelands and journeyed half a world away. A combination of poverty, landlessness, harsh climate and a desire for better opportunities propelled them onto a ship for 3 months at sea and never to see their family ever again.

I can’t even imagine that, and I can imagine they experienced some trauma as a result of the intense separation. And as we now know, intergenerational trauma is not easily healed.

(I feel that I owe a disclaimer here. In expressing compassion for my ancestors actions, I am not excusing them, nor condoning the part they played in displacing tangata whenua and benefitting from the theft of their lands. It’s a very complex history, but one that I am choosing to view with love and compassion, as well as political critique.)

2020: Funnily enough, it took the lockdowns to really connect me with my tāne’s (partner’s) marae, through running free online te reo Māori yoga classes. A bunch of my tāne’s whanaunga - rellies came to my online classes, and when we came out of lockdown they invited me to teach in-person classes at the marae to a group of Iron Māori aunties. I felt incredibly lucky to share something that I valued with the hapū, and I’ll always treasure the connections that were made through this kaupapa - initiative.

2022: When my partner and I broke up earlier this year, I grieved for more than just a broken heart. Yup, there was the usual loss of dreams, hopes, gardens and love. But there was also my connection to his marae, to his whanaunga, and to our home in which tikanga and reo comfortably resided. The part of me that felt so at home in his world really mourned that loss, and what opened up was a giant chasm in my own identity.

My connection to te ao Māori suddenly seemed very fragile, as if hanging by a thread, possibly only connected by my teaching mahi at kura, and my loyal friends.

So when I went on my 10 day Vipassana meditation retreat in July (which I’ve written about here) I had no idea the incredible gift I would end up receiving. I honestly thought I was just going to get some peace and happiness.

But what I really got was a deep sense of belonging.

Something I’d been searching for my whole life outside of myself, and I finally found it within.

And it was such a relief to feel like I was home. Home in my body, home in my mind, home in my soul.

Nowhere to be, nowhere to go, except the present moment, here, now, with myself. Filled with a sense of deep love and compassion for myself, and for all people.

So a month or so ago when I got called out on social media for cultural appropriation by people I don’t know, yes I was hurt. Yes, I felt rejected, and was definitely triggered back to early childhood experiences of bullying.

It seemed to throw salt in the wound of my already painful break-up, and for a week or so I felt incredibly lonely and vulnerable.

But do you know what? It didn’t last long. Because I no longer have the same unmet need to belong to a culture or people group outside of myself, nor to seek their approval.

And I can understand exactly what my critics’ were angry about.

I represent the very pinnacle of white privilege (with the exception of being a woman, not a man), and as such, I have already had the biggest head-start in life.

I’ve already got great health, no debt, money in the bank, an inheritance one day when my parents pass on, a university education, and I am not on the receiving end of systemic racism.

AND I also am endowed with a lofty taonga- treasure, te reo Māori, which many Māori have not had the opportunity to learn. I have been dealt an incredibly lucky hand in life.

So for my critics, possessing a Māori business name, not just any Māori name, but an especially tapu one like Mauritau, has been like throwing salt in the wound. Privilege on top of privilege. And I really do get how offensive my actions have been for some.

I apologise profusely, and I am so sorry for the hurt that this has caused. I am in the process of finding a new, culturally appropriate name for my business, and returning ‘Mauritau’ to tangata whenua.

A couple of weeks ago I was visited by an old uni mete - mate of mine, who came to receive a massage but also to give me some guidance, given what I was dealing with.

What she said to me that day will always stick with me, and I'm eternally grateful for her strong, loving words.

She said, "Laura, we love you and we appreciate all that you've done for our people, but you've done your time in te ao Māori."

Had I heard those words a few years ago, I might have had a very bruised ego.

But you know what? Her words felt like a relief. I took them to mean that I could stop striving to fit in. To carry a burden that maybe wasn't mine anymore to carry. I'm reminded of the saying: "If you love something, let it go..."

And as I look back over my awkward years of trying to fit in and never really succeeding, I have a great deal of compassion for myself. Because I know now that it took all that striving and failing and trial and error to lead me to the path that I am currently on.

And this doesn’t mean that I’m some enlightened soul now that is somehow immune to social and cultural forces.

I am still muddling my way through my own cultural expression of who I am, and how I relate to tangata whenua - people of the land, as tangata tiriti - people of the treaty, here in Aotearoa. And I may spend the rest of my life screwing up, and doing things ‘the hard way’ as my mum always says that I do.

But it does mean that I have a greater sense of freedom, peace and presence in my mahi.

That I no longer am doing anything in te ao Māori out of a need to belong, or to have my fragile ego validated.

But if and when I am contributing to te ao Māori as tangata tiriti, may my humble contributions be offered as a pure expression of love and gratitude.

That is my heart’s desire.

He aroha whakatō, he aroha puta mai ~ If kindness is sown, then kindness is what you shall receive.

Mauri ora x

If you are Pākehā/Tauiwi and you would like support to write your own culturally appropriate pepeha, here are some useful resources written by my very clever uni classmate Donovan Farnham nō Ngai Tūhoe:

Also, I'm around if anything I've shared has resonated, or if you want to kōrero about your own journey in this. Get in touch.

Thanks so much for sharing, this helps ❤️

I am sitting having a cup of tea with my 80 year Mother, whom for the past twelve years has worked as a teacher aid at our local area school. She goes to work at 7am and provides breakfast club to all, and contributes to Supported learning Students during the school day, also works in the school Hospitality Class.

In the past few weeks our conversations have revolved around her being asked to provide a Pepeha as a Staff member.

She feels pressured to do this, as she has no Whakapapa to any Aotearoa tribe, and her family connections are of

English, Irish, Scottish Descendants.

She trained at Teachers training College in 1964, and has never experienced this controversy in…

I had the same questions as to where I fit into Aotearoa. I struggled til my 40s to finally make sense of my place here and stand tall and proud. My people arrived in NZ in the 1850s. So a few generations as kiwi peoples have passed. I have no maori ancestors, and wondered about my place and belonging in NZ, as I felt the word Pakeha didn't describe my upbringing or thought patterns or my feelings and love for the whenua and peoples here. I spent most of my free time in the Ngahere hunting, to help renergize my wairua in between mahi. I worked in prison for 21 years and culturally I grew as I gained knowledge and…

I would love to kōrero more With you about this! I am just beginning that questioning journey for myself, my sense of belonging as a pākehā wahine in Aotearoa.